The Tourmalet

Name the mountains you most want to do. Ask any cyclist to name the top 5 cols they want to climb, anywhere in the world. One name will appear on every list, and usually near the top – the Tourmalet.

It is not the most difficult, longest, steepest but it has all those things, and something many of the others don’t: grandeur.

Inwardly, we both knew, the training had been for this. The rides so far – preparation.

After a fitful nights sleep we woke early to a sky of stars. After this many years the pre-ride preparation is routine, though with a hint of nervousness today.

We started early in the semi dark when it was still cool, dressed for the warmth expected later in the day. We took the bike path rather than the road as it runs through the middle of the fields that surround the house. The fields are of corn, which is confusing given there is never any to buy in the shops. The crops supported by the irrigation channels at regular intervals, running with water sourced from higher up the mountains. We are starting right at the bottom of the valley, so the road runs FLAT for the first few kilometres.

The Tourmalet is considered to start at Luz Saint Sauveur and is 21km long. For us, starting from our house in Lau Balagnas it will be 35km, more than 30 of it uphill. Anyone care for a Lappo or two before we tackle the Tourmalet?

Joining the road we can look down on a mountain stream as we head into a gorge. The stream is flowing fast, seems full of energy, youthful almost, but intimidating with the sense that all it would take is a days rain for it to break it’s banks. It is very uplifting to have next to you a display of energy. I’m feeling good riding up these first few hills, feeling ready for the fight, sitting up straight in the saddle, ready to ‘ave a go’.

We take the first 15km easy, making sure we spin rather than strain.

At the top of the gorge, we cross a bridge, above a dam. Disheartenly, the mountain stream is dammed. Exuberance must be controlled in Europe – that stream will never break it’s banks.

Leaving the gorge we ride into Luz Saint Sauveur, turn left at the roundabout in the middle of town, and start the climb. There is little signage signalling the start of the climb, unlike other famous climbs, to the extent that at the start Pam is doubtful we are even on the right road.

The views already are stunning. Not a cloud in the sky. One side of the valley lit up by the sun.

To quote Michael Rogers, as I have before, when he won a stage of the Giro atop the Zoncolan: “These are the days that dreams are made of”.

I get passed, but have no thoughts of picking up the pace, so he slowly pulls away.

My knee starts to hurt. My cadence is 60rpm. So 60 times per minute, for just under 2hrs, I will push down on my right leg, and it will hurt.

The higher we climb, the more the view unfolds, the mountains ahead rising above the ridges running down off the surrounding mountains and as the road twists we see into the side valleys.

The climb is as reported, unrelenting, providing little respite. I begin to question the ratios I am running, and wonder if I should have swallowed my pride and fitted a bigger cluster. I would have been slower at the bottom of the hill, but faster through this mid section where fatigue is now setting in. Many of the roads in the Snowies sit at either 8% or 10%, exactly, for long stretches. It is as though an engineer placed a ruler across the map, drew a line, and said ‘that is where the road will go’, with little feel for the contours of the land and the potential for undulations. There are long stretches of the Tourmalet that feel that way.

I would like to understand why in some places a road will hold to a consistent 6%, and in others 9%. It is not as simple as the size of the mountain. Is it due to the topography, and whether there is space for a flatter road, the geology, or why the road was first built and the traffic it was built for?

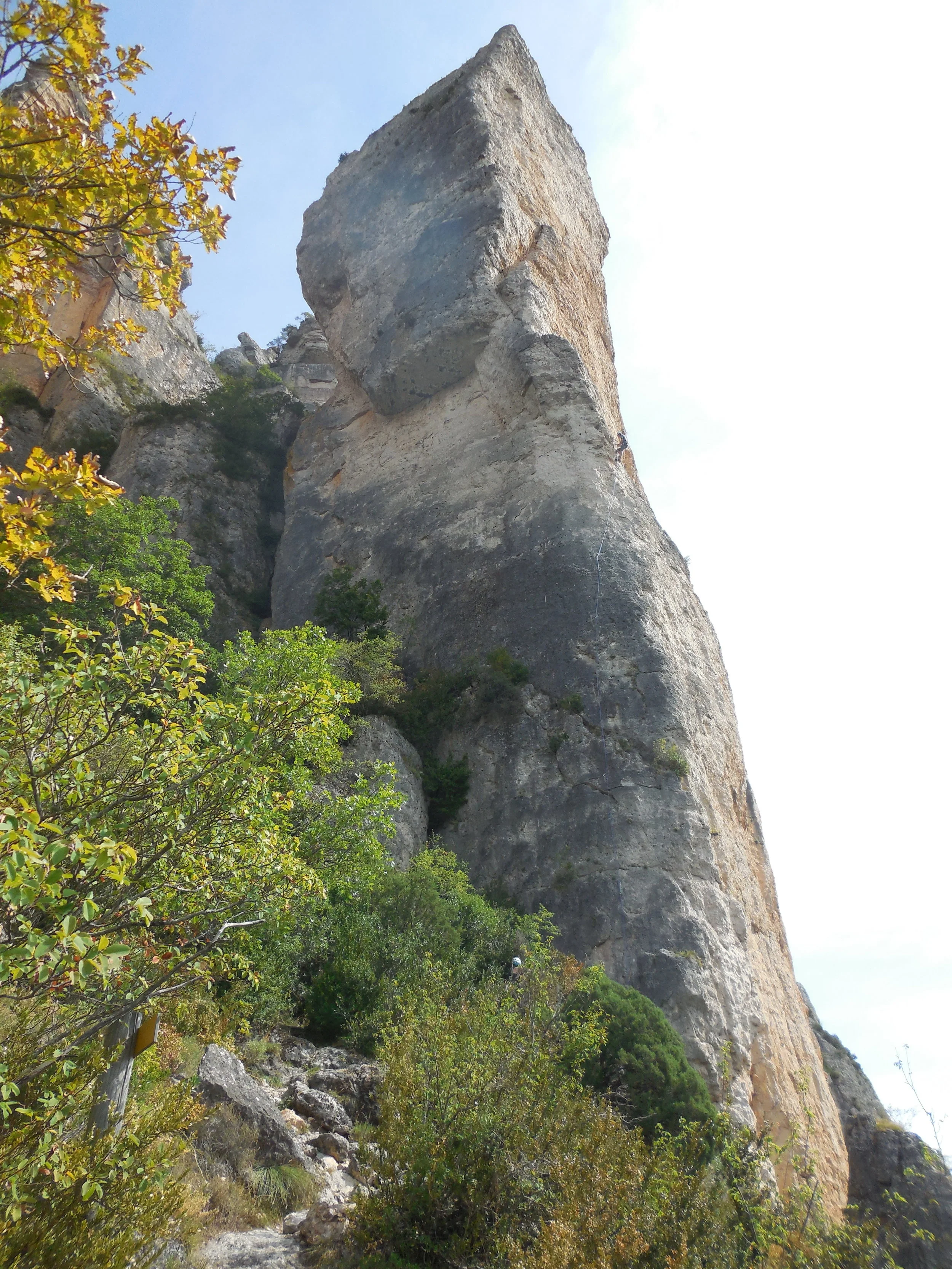

With 5km to go, the questioning begins: why I am doing this. Not why I am here, but why am I doing this – riding up this hill. I know why I am here – the Pyrenees are spectacular. But why am I doing this? I don’t normally ask these questions. And today I am struggling for answers. To avoid the question, I look around, at the setting. There are scree slopes leading up to great cliffs. And where there is a smattering of grass over the scree, there are sheep, with bells on, grazing. This is Europe, even when you are on the side of a mountain, you are never truly remote.

What is the technique for riding these hills people often ask: ‘with those cleats you can pull up and push down can’t you’. Just try pushing your body weight up a steep incline by pulling up with your leg. The technique is this: you smash your foot against the pedal until it hits the bottom of the stroke, and then you smash the other foot, and repeat, until brain, butt and legs have gone numb.

When there is 1km to go, I know that I will make it. There are no thoughts of ‘winning’ or ‘beating’ the mountain, merely of completing the activity. No one can beat the mountain, and I certainly haven’t today.

500m from the top – thoughts of getting off cross my mind. Briefly! The steepest section of the last 30km of climbing is now, when the legs have had no rest for 2hrs.

I arrive at the top to no fanfare, a breathless “Sweeney” muttered as I pass the sculpture placed on the crest of the col. Pam joins me soon after, by which time the col is abuzz with cyclists and tourists. Our reward, a very nice chocolat chaud: and the deep satisfaction from looking back down the mountain. We were not the fastest, and few suffered more than Pam due in part to a pedal broken part way up that meant her foot would unclip without warning, typically on the steepest sections.

The descent is not fun. Through all the pain of the ascent you look forward to the trip back down, when you are free to fly and glide like a bird. The road is a patchwork of recent repairs creating that jolting feeling one gets driving down the concrete section of Parramatta Rd. This of course unsteadies the bike, which in turn unsteadies the mind making it hard to corners with any real commitment. And then there is the traffic. The road in places is not much wider than one motorhome, so there is no margin for error when exiting a corner. Add to that the now continual stream of cyclists pounding themselves up the hill, the motorists, 4 wheel and two, overtaking them at every opportunity and even when there is none: floating across to the imaginary centre line is fraught with danger. Eventually the road widens and the traffic thins and we can whiz down.

Back at Luz Saint Sauveur we remove our jackets added for the descent and then head to the gorge we rode up. The wind has now changed direction, and the expected fast descent through the flowing corners has become an effort: a pedalling descent that saps the last of my energy. A feeling of being cheated from a prize becomes stronger on a descent the more the legs become fatigued.

The Tourmalet can now be moved from one list to the other.

The numbers:

Distance: 71km

Height Gained: 2,400m